Program Notes for October 21 & 22, 2022

Rhapsody in Blue

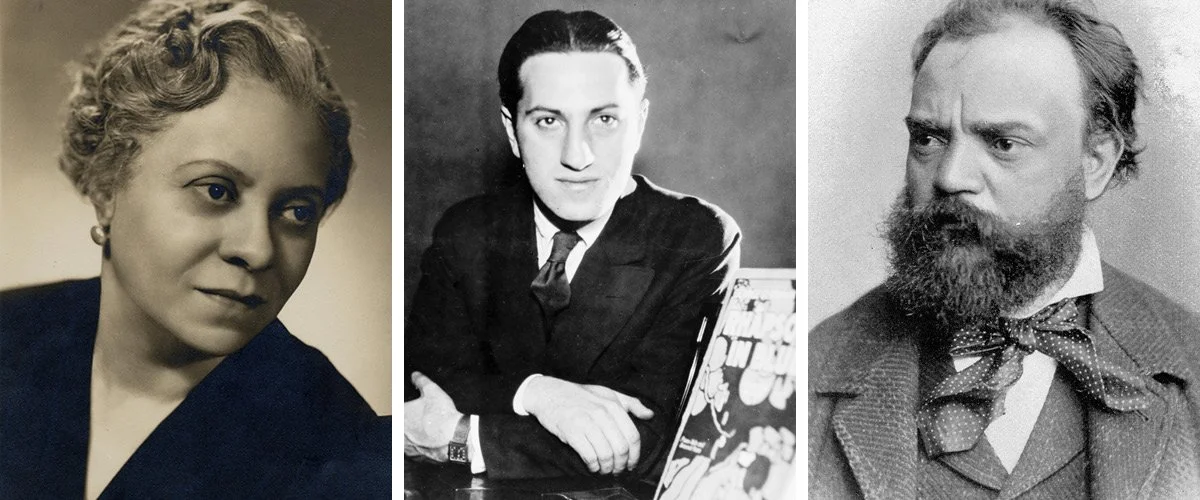

Florence Price

Concert Overture No. 2

Composer: born April 9, 1887, Little Rock, AR; died June 3, 1953, Chicago

Work composed: 1943

World premiere: undocumented

Instrumentation: piccolo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, harp, and strings

Estimated duration:15 minutes

As the first Black female American composer to have a symphony performed by a major orchestra, Florence Price enjoyed considerable renown during her lifetime. Her compositional skill and fame notwithstanding, the entrenched institutional racism and sexism of the white male classical music establishment effectively erased Price and her music from general awareness for decades after her death. In 2009, a large collection of scores and unpublished works by Price were discovered in a house in rural Illinois. Since then, scholars, musicians, and audiences have been discovering Price’s work and her rich legacy.

The daughter of a musical mother, Price was a prodigy, giving her first recital at age four and publishing her first composition at 11. During her childhood and teens, Price’s mother was the guiding force behind her piano and composition studies. Young Florence entered New England Conservatory in 1903, at 16, where she double majored in organ performance and piano pedagogy. While at NEC, Price also studied composition with George Whitefield Chadwick. Chadwick was an early champion of women as composers, which was highly unusual at the time, and he believed that American composers should incorporate the rich traditions of native American and “Negro” styles in their own works. Price, already inclined in this direction, was encouraged by Chadwick, and many of her works, including tonight’s Concert Overture No. 2, reflect the expressive and distinctive sounds of Negro traditions, particularly the spirituals, ragtime, and folkdance rhythms whose origins trace back to Africa. This overture features the spirituals “Go Down, Moses,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” and “Every Time I Feel the Spirit.”

George Gershwin

Concerto for Tabla & Orchestra

Composer: born September 26, 1898, Brooklyn, NY; died July 11, 1937, Hollywood, CA

Work composed: Gershwin wrote Rhapsody in Blue in the first three weeks of 1924

World premiere: Gershwin was at the piano when Paul Whiteman’s Orchestra premiered Rhapsody in Blue at Aeolian Hall in New York City, on February 12, 1924

Instrumentation: solo piano, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, alto saxophone, tenor saxophone, 3 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, gong, glockenspiel, snare drum, celesta, triangle, banjo, and strings

Estimated duration: 15 minutes

Rhapsody in Blue introduced jazz to classical audiences, and simultaneously made an instant star of its composer. From its iconic clarinet glissando to its brilliant finale, Rhapsody in Blue epitomizes the Gershwin sound, and transformed the 25-year-old Tin Pan Alley songwriter into a composer of “serious” music.

On January 4, 1924, Ira Gershwin showed George a news report in the New York Tribune about a concert put together by jazz bandleader Paul Whiteman, grandiosely titled “An Experiment in Modern Music,” that would endeavor to trace the history of jazz. The article concluded, “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto.” This was certainly news to Gershwin, who was then in rehearsals for a Broadway show, Sweet Little Devil. Gershwin contacted Whiteman to refute the Tribune article, but Whiteman eventually talked Gershwin into writing the concerto.

In 1931, Gershwin described to biographer Isaac Goldberg how the musical ideas for Rhapsody in Blue first emerged: “It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer … And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper – the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end … I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

At the premiere, Gershwin’s unique realization of this “musical kaleidoscope of America,” coupled with his phenomenal abilities at the keyboard, wowed the audience as much as the novelty of hearing jazz idioms in a classical work.

The opening clarinet solo got its signature jazzy glissando from Whiteman’s clarinetist Ross Gorman. This opening unleashes a floodgate of colorful ideas that blend seamlessly. The pulsing syncopated rhythms and showy music eventually morph into a warm, expansive melody à la Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Antonín Dvořák

Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, “From the New World”

Composer: born September 8, 1841, Nelahozeves, near Kralupy in Bohemia (now the Czech Republic); died May 1, 1904, Prague

Work composed: 1892-1893 in New York City

World premiere: Anton Seidl led the New York Philharmonic on December 16, 1893, at Carnegie Hall.

Instrumentation: 2 flutes (1 doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, cymbals, triangle, and strings.

Estimated duration: 40 minutes

Antonín Dvořák began his Ninth Symphony in December 1892, shortly after he arrived in America, and completed it the following May. During his three-year sojourn in New York, Dvořák explored the city, watched trains and large ships arrive and depart, fed pigeons in Central Park, and met all kinds of people. Late in 1892, Dvořák wrote to a friend back home, “The Americans expect great things of me. I am to show them the way into the Promised Land, the realm of a new, independent art, in short, a national style of music! … This will certainly be a great and lofty task, and I hope that with God’s help I shall succeed in it. I have plenty of encouragement to do so.”

Dvořák was also introduced to a great deal of American folk music, including Native American melodies and Negro spirituals. However, he did not quote any of them in the Ninth Symphony. Dvořák explained, “The influence of America can be readily felt by anyone with ‘a nose.’” That is, hints of the uniquely American flavor of this music are discernable throughout, as Dvořák made use of the syncopated rhythms, repeated patterns, and particular scales common to much of America’s indigenous music. But the Ninth Symphony is not a patchwork of previously existing materials, and all the melodies in the Ninth Symphony are Dvořák’s own (including the famous English horn solo in the Largo, which was later given the title “Goin’ Home,” with accompanying text, by one of Dvořák’s New York composition students, a young Black composer and baritone named Harry Burleigh).

“I have simply written original themes embodying the peculiarities of Indian music, and, using these themes as subjects, have developed them with all the resources of modern rhythms, harmony, counterpoint, and orchestral color,” Dvořák explained. As for the title, “From the New World,” Dvořák intended it as an aural picture postcard to be mailed back to friends and family in Europe and meant simply “Impressions and Greetings from the New World.”

At the premiere, the audience applauded every movement with great enthusiasm, especially the Largo, which they cheered without pause until Dvořák rose from his seat and took a bow. A critic writing for the New York Evening Post spoke for most when he wrote, “Anyone who heard it could not deny that it is the greatest symphonic work ever composed in this country … A masterwork has been added to the symphonic literature.”

© Elizabeth Schwartz

NOTE: These program notes are published here by the Modesto Symphony Orchestra for its patrons and other interested readers. Any other use is forbidden without specific permission from the author, who may be contacted at www.classicalmusicprogramnotes.com